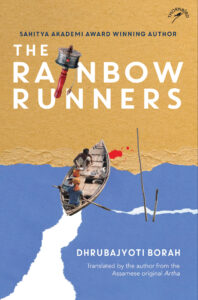

Exclusive Interview Of Author Dhrubajyoti Borah On The Rainbow Runners

One of the most innovative and fearless voices in Assamese writing now is Dhrubajyoti Borah. Borah is an Assamese-English writer who has authored around twenty-five novels and novellas. His investigation into the tragic and troubled reality of modern Assam, marked by insurgency and counter-insurgency, is celebrated as one of the greatest literary works of the modern age in the Kalantar trilogy. His novel Kalantarar Gadya, written in Assamese, has been translated into Elegy for the East (2020; Niyogi Books).

Among Borah’s most well-known non-fiction publications is a highly regarded book about the Moamoria uprising in medieval Assam. Translations of his writings are available in Malayalam, English, Bengali, Hindi, Bodo, and Nepali. In 2009, he was honored with the Sahitya Akademi Award.

The Kolkata Mail correspondent Priyanka Dutta caught up with the writer on his new book The Rainbow Runners. Excerpts..

Can you share with the readers a little bit about the story?

It is not always easy to speak about one’s writings. This story is basically of a lost generation who had lost their innocence, dreams, and the meaning of life due to the situation they were forced to live, by tragic and turbulent times they had to face and cope with

An ordinary youth (Sriman), a small-time writer, student activist, and then a jobless loafer happened to see a secret killing on the bank of Brahmaputra which not only terrified him but made him a paranoid wrack. Unable to share his dread with anyone he floated through life into the murky world of journalism and then into the world of the dadas. Those dasas were the erstwhile underground leaders who surrendered to the Government and then started working for the state against their past colleagues and organization. In this situation of distrust and violence produced by terror and counter-terror, he again came face to face with the tragic reality of the times – another secret killing! It completely unhinged him and he lost his sanity.

Fate brought him to the Himalayas after a long treatment in Delhi. He entered into a small tracking company (owned also by the dadas) in a small matchbox-sized Himalayas town and it was during his stay in the Himalayas he learned to come to terms with life. He came to find a new way, discovered the eternal teaching of the Buddha, met and related with people, and gained an insight into the tragedy of Tibetan refugees and their improbable dream of restoration of their homeland someday.

It was here he found love in all its beauty and sorrow, felt its rejuvenating elixir, its promise of redemption of his shattered and fragmented life. He also experienced heartbreak when the person he loved had suddenly become a Buddhist nun following her quest for meaning in life.

Amidst the decay that had set in the society and the ruins of his personal life Srimans quest for meaning in his existence reflects a universal human quest and longing. That’s what I have tried to catch in this story.

Why is the book named The Rainbow Runners?

The original name in Assamese was ‘Artha’ – the meaning.

It is the story of an entire generation of youth of my state who out of both romantic and nationalist convictions ran after a dream. They thought that independence from India would end the mainland exploitation of man and resources and with the riches and opportunities present here, a more equitable, egalitarian future for its people could be built up. This dream, however impossible, propelled thousands of youth in a path of arms struggle, and underground arms politics, into ideologies that led them to great sacrifices and at times, to even greater sufferings. They took on a modern state and its military might which not only violently suppressed opposition but accommodated such people at a personal level and assimilated them, a deadly combination one had to face.

It is in this context, that the youth, the insurgents all appeared like the ones who not only ran after an ephemeral, impossible dream like a beautiful rainbow but also tragically believed in the mirage and tried to sell this dream to others. The failures that eventually came with the inevitable suffering and sorrow spurred the Rainbow runners into imagining other realities.

Your stories revolve around insurgency and Assam. Why do you feel the need to write on such topics?

A society, a people who had not gone through the times of insurgency, the suspicions, suffering, violent retribution, the terror unleashed by both state and non-state terrorism, the pull of centripetal and centrifugal forces tugging at their heartstrings don’t experience the tragedy of social upheavees. That they may learn and realize it is one of the purposes of my writing on those topics.

So I first wrote a trilogy on this broad background – The first book (an elegy for the east – Niyogi book) which dealt broadly with genesis, and the second book, this one, which deals with the tragedy of shattered dreams (The Rainbow runners – Niyogi Thorn birds) and the third book (yet to be published) that shows the effect of such violence on the rural non-combatant people and the situation of suffering and greed that got born under such circumstances.

There is a fourth book too ‘The Sleepwalkers Dream’ which shows the aftermath of a military defeat and a perilous journey of insurgents through terror on an uncertain path towards (?) redemption (published by Speaking Tigers). Together they present my total quest about the human condition you come to meet under situations of modern-day insurgency. But the rest of the topics on which I write are not on insurgency.

How much time did you take to write this book?

It took me about two years.

When writing on such factors like insurgency, what do you have to keep in mind as an author?

Our younger generations either do not know this deeply troubled past of insurgency with its senseless violence and killings or are not interested in it. In addition, those with memories of the tumultuous times are also forgetting them or are themselves slowly fading away. That’s how my good friend and author Sanjay Hazarika wrote (strangers in the mist) and he added poignantly “That the past is our shadow and not just the moment behind us”.

My reason for writing on insurgency is exactly this – it had been a part of our collective experience and we can’t afford to forget it least we were forced to relive those times. Writing about insurgency for me is part of the eternal struggle of memory against forgetting.

There are no real heroes in this story about insurgency neither there are villains. Clashes occur between people who believe in what they do, and do what they perceive to be right. So an author has to deal each of his characters with empathy and sensitivity.

Will your next book be also around such topics as insurgency and counter-insurgency?

No, I don’t think so. I have dealt with the subject quite extensively and possibly have nothing more to say about it that I have not said in the ‘quartet’ of my novels.

After these four books, I have written on the Kalaazar pandemic that razed Assam from 1900-1940 where lakhs of people died. It was written before Corona, the pandemic, but I am really surprised to see how situations could be quite similar. My new novel ‘Inner landscapes’ has the Burmese invasion, as the backdrop, and the latest ‘Pilgrimage of Donkeys’ is an exploration of the situation of early post-colonial Assam, which is intertwined with the Chartist movement of England. These two post-colonial and to an extent post-modern writings (that’s what the critics said, the author didn’t) are the new subjects and they don’t have any insurgency in them.

Do you feel more young writers should write on these topics like insurgency and others?

I don’t know honestly. I would be happy to see them delve into hitherto unexplored human relations of the period. Such things as insurgency, ethnic strife, and violent political struggles like Naxalism attract the young and not-so-young writers who usually bring out newer perspectives to age-old problems. One can only hope that they continue to do so.